One of the annoying things about living halfway up a mountain is that we lose power more often than if we lived in a normal suburban home. This is partly because the area is more sparsely inhabited and partly because winter storms up here can be pretty ferocious wind-wise. Add to this the fact that sometimes our neighbors do silly things that blow up transformers, and occasionally a power pole is taken out by an errant driver as the roads up here are not what one would call straight.

Since first moving here, we’d been discussing and researching options for mitigating all the problems that accompany losing power for a few hours or even a few days. Originally we really did think a big old 22kWh diesel generator was going to be the way to go. We even had a concrete pad put in where we thought it would eventually reside.

Why diesel you ask? Well, unlike just about all the other properties up here, our place does not have propane. When the house was built in 1966-67 it was originally just electric for appliances and diesel for heat. Back east, diesel is referred to as heating oil, but out here it’s just dyed diesel, the same stuff we can put in our tractors, the excavator, skid steer, etc. Said diesel can also be used to run a generator without issue, but regular readers will know that two years ago we pulled out those twin diesel furnaces and replaced them with mini-splits.

Since everything here is now electric, it didn’t make sense to go backwards and get a big diesel generator, especially as we’d have to trench and lay in conduit to handle the electrical feed up to the house. Plus the low-end estimates for buying even a used one and getting it all sorted were around $18K.

One of the few good things the previous owners of our place did was install a big solar array at the top of the south pasture, just off the southwest corner of the Great Wall. Since we have solar, one would think that if grid power is lost during daylight hours, we could just power the house off the solar. However, grid-tied systems, which are the most prevalent sort, are not meant to work like that due to issues like backfeed–the term for sending power back down the line which you really don’t want to be happening when linemen are trying to fix a transmission issue. Plus there’s the whole issue of where all that excess power is going to go if the grid is down. Then there is the fact that when the sun isn’t in the sky and power goes out, solar of any sort is, by itself, of no use.

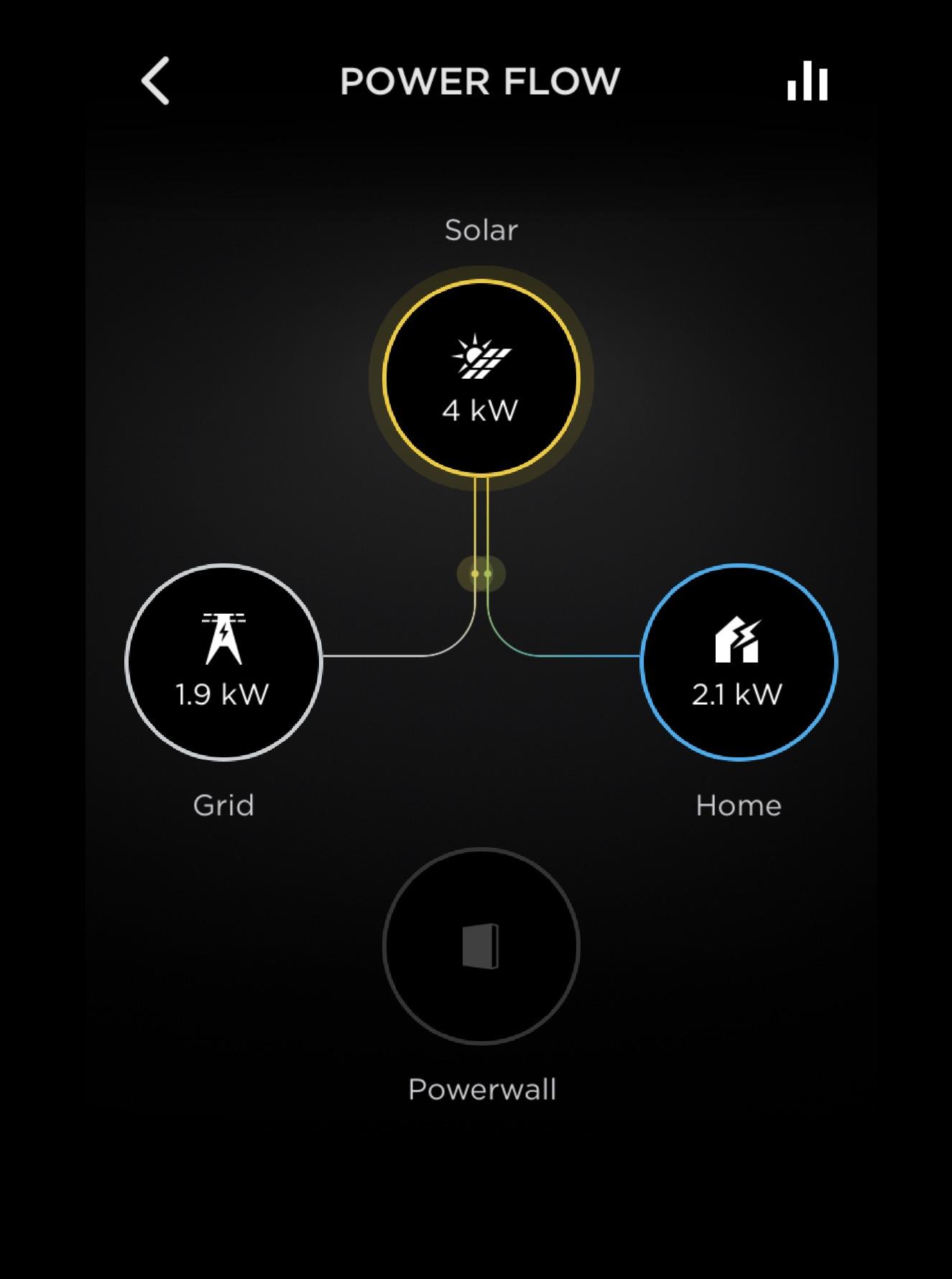

Enter the power wall. For those who have heard the term but aren’t quite sure what it means…imagine a battery backup for your house. You may have a UPS that your computer connects to and then the UPS connects to a power outlet. That way, should you lose power, your computer stays up and running–especially handy when you might lose power for only a few seconds or just a couple of minutes. A power wall functions much the same way–if grid power goes out, your house stays up and running as it pulls what it needs from the batteries that make up the power wall. Since a power wall provides a convenient storage point to send excess power to if/when the grid goes down, it solves the issue of backfeed.

That’s not all though, as power walls also have some really cool extra-special bonus features. Unlike the UPS attached to your computer which keeps its battery charged by pulling current from the outlet, a power wall can be charged via sources other than the electric service provided by your standard utility company. That means if you have a solar array, that excess energy your array generates can be used to charge up your power wall. This is especially useful for when you are capped in terms of how much electricity you can feed back to your utility and get paid for.

Utility companies are in business to make money for their shareholders. While many people wish this were not true, that (at least in California) is the way things are. So while our solar array happily turns out many, many electrons–a good percentage of which go back down the mountain to help power other stuff–we don’t actually see much in the way of a financial reward for what we generate. Our utility company does what is called a “true-up” each year where we pay any balance due. This means all kWs we have pulled from the grid, minus whatever our utility deigns to pay us for what we generated and then adding in the administrative costs ($10/month/per meter) associated with our meters. (Regular readers will know our place has two meters as thirty or so odd years ago there was apparently a mobile home out near the main gate.)

| Year | True-Up | Notes |

| 2016 | $1600 | Diesel Heat |

| 2017 | $740 | Diesel Heat |

| 2018 | $570 | Diesel Heat |

| 2019 | $1330 | First year on electric mini-splits |

| 2020 | $770 | First year with power wall |

So just from the above numbers it looks like we’re spending more money on energy since ditching our old diesel furnaces, but what you don’t see is that from 2016 to 2018 our cost for enough diesel to heat the house was between $800 and $1200 a year. The 2019 uptick was thus marginal, and as you can see, with the addition of a power wall a year later, our electric costs had fallen back down to what they were when we were still on diesel.

Before I get back to power walls and why they’re so cool it’s time to take a sidestep and talk about why it is now more expensive to do your laundry at night vs during the day.

About twenty years ago, the utility companies out here were hard pressed to keep everything running, especially during hot summer days. Office parks, residential homes and the booming data-center build-out mean a lot of energy was spent keeping everything cool. It wasn’t uncommon for data centers to have very large diesel generator plants and to use them as a selling point when luring potential customers. Sure, peering points were great, but would your servers stay up when the brownouts rolled through? That all changed over the next ten years as solar arrays atop every other roof became standard. Ample energy was now available to cool offices and data centers during the day. This led to an inversion on when it costs the least to do a load of laundry. (And yes CA technically does Net Metering–but not actually since the generation payment vs. buyback cost are not equal as they buy at wholesale and sell back at a much higher rate.)

See, back before solar was so prevalent, it was much more expensive for the utility companies when people did their washing during the day because that’s when power was scarce: and keep in mind that some days’ generation was barely meeting demand. Utility companies wanted a way to better manage this and if possible, to make some extra money from it, as from their perspective, it would be great if they could charge more for their product when demand was high.

So they tackled the problem with two key ingredients: smart meters and variable rate billing. A smart meter, as just about every resident in California knows, is a meter that transmits your energy usage wirelessly. No more meter-readers dodging nippy dogs to pop around behind your house each month to jot down your usage numbers–an added bonus for utility companies in that they no longer have to employ such workers, which helps their bottom line. These smart meters can pump out usage information at regular intervals, if not continuously, which means utility companies can easily see how much energy each meter, or node, attached to the grid is using. So if a utility company knows how much you’re using at a specific time and demand at that time is high, well then, they can charge you more. That is what is called in the industry “variable rate billing.”

So getting back to the laundry inversion: before solar was a big deal and feeding millions of kWs back to the grid, on a hot summer day it was much more expensive for a utility company if someone did their laundry during the day. (You may have never noticed this fact, but the utilities sure did.) By 2010 though, this fact was no longer the case; the surge in solar installation meant reliance on traditional hydro/coal plants to create electricity was beginning to ebb. The influx of power from solar arrays during the daylight hours when the utilities had once struggled to meet demand meant the issue of brownouts just faded away.

Thus it was no longer costing the utility company more if you wanted to do laundry during the day. Instead it cost more if you did your laundry at night because that is when all that almost-free solar power was no longer coursing through the grid. Yet the utility companies had planned for this because now they had smart meters and thanks to smart meters they could simply use their now almost perfect variable rate billing setups to pass that cost on to the consumers.

And that is why it now costs you more to do laundry at night.

What does this have to do with power walls you ask? Well, the additional key benefit of having a power wall is that once the sun goes down and your house is no longer pulling its energy from solar, a power wall can be used for your power needs instead of the grid. That’s right–instead of doing a load of laundry after sunset and being charged the nighttime rate, you can draw the power you need from your power wall.

Now granted, there are some limitations, namely a power wall is sized based upon the generating capacity of a solar array and projected usage of a building. It is also common to only draw a power wall down to around 50% capacity at night to ensure that if an actual outage occurs, your home will not be impacted severely. But there is also an option to allow a power wall to be charged via both your solar and the utility grid. This is especially useful when your utility company may do planned shutdowns when high winds are forecasted during fire season.

By now you’re probably wondering about the details of our power wall, as obviously we now have one. For that however, you’re going to have to wait for the next post as my fingers are tired after so much typing.